Engineering Archie – The Godfather of Stadium Design

- Written by

- David Ross

- Listed in

- Posted on

- 25th Nov 2019

For almost thirty years prior to his death in 1939, Scottish architect Archibald Leitch was the undisputed Godfather of stadium design. Although far less acknowledged for his design skills and timeless innovation, he had been a Glaswegian contemporary of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. In 1899, while the latter was finishing the first phase of Glasgow School of Art, Leitch was completing his first stadium for his boyhood heroes, Rangers. How he secured this commission remains unclear, although his freemasonry background, and his decision to work on the project for free, might offer the most obvious clues. His previous work included Victorian sheds in Glasgow and Tea Factories in Ceylon. The A-listed Sentinel Works in Polmadie is still standing, but beyond the elaboration of a facade and the strict regularity of an open structural bay, there is little to hint at an aptitude for these new building types. He did however retain a membership of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland. Arguably, it was an interest in the more structural aspects of building design that found a commercial outlet for his growing expertise. Little in the way of precedent existed, so the football stadium work of Archibald Leitch in the first four decades of the 20th Century was undeniably ground-breaking.

But Leitch’s fledgling reputation suffered an immediate and tragic setback. His Ibrox Stadium was only three years old when 26 people were killed and over 150 injured following the collapse of a bank of wooden terracing. Such a catastrophic failure could’ve destroyed him, yet despite the renovation work being placed elsewhere, he regrouped. He rethought the appropriateness of certain materials and their loadbearing capacities. He became determined to make football stadium design safer. In cutting out a leading position within a niche market, a refocused Archibald Leitch remained in high demand, and over the next forty years, he became Britain's foremost football stadium architect. In total he was commissioned to design more than 20 stadiums in the United Kingdom and Ireland between his inaugural work at Ibrox and his death in 1939 at the age of 73. Some of the most notable grounds in the game’s history feature in this list: The Art Deco design of Highbury, the elaborate Holte End stand of Villa Park (completed after his death by his son, Archibald Junior), White Hart Lane, and of course, Hampden Park. At his peak in the 1920s, 16 of the 22 English First Division clubs played in grounds Leitch had designed. As perhaps the best measure of his impact and legacy, six of the eight grounds used for the 1966 World Cup Finals in England were Archibald Leitch creations.

Influenced by his early work on the industrial buildings, Leitch's stands were initially noted for their resolute pragmatism rather than being aesthetically elegant. Typically, his stands had two tiers, with criss-crossed steel balustrades at the front of the upper tier. They were covered by a series of pitched roofs, built so that their ends faced onto the playing field. The span of the main roof would be distinctly larger, frequently incorporating a distinctive pediment. His first project in England was the design and construction of the John Street Stand at Sheffield United’s Bramall Lane. It provided 3,000 seats and terracing for 6,000 supporters. The stand was dominated by a large mock-Tudor press box. Despite suffering extensive damage in the Sheffield Blitz, Leitch’s stand survived for almost a century.

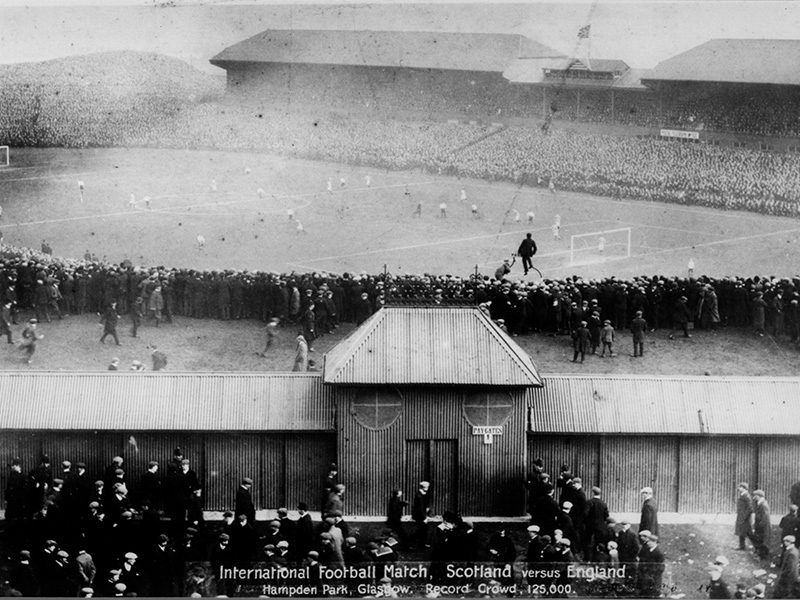

During one week in April 1937, almost 300,000 supporters jammed themselves into Hampden Park for two British Championship matches. From the supporter’s perspective, a different intensity to the Scotland v England rivalry existed then: “…in those days it was fun and banter, no viciousness or any animosity whatsoever, it was a party time”.

When the North Stand was completed during that same year, Leitch had calculated the capacity of Hampden Park to be a jaw-dropping 183,724. Viewing the famous aerial shots of these games, it’s now astonishing to acknowledge that the integrated issues of crowd safety, transport infrastructure and the policing of vast numbers of people are relatively recent considerations. Ironically, Leitch’s Ibrox Park was the awful catalyst for the subsequent revolution in stadium design. Following the disaster in January 1971 when sixty-six people lost their lives, trampled and crushed on the unrelenting concrete of Stair 13, plans were considered to modernise; to prevent a similar catastrophe from happening again. It would take almost twenty years and another tragedy at Hillsborough before the Taylor Report into safety at sports stadia made change universally necessary and compulsory.

Few examples of Archibald Leitch’s extensive body of work now remain intact, but those that do – the main stand at Ibrox, the uniquely quaint clock-corner at Craven Cottage, the original, now unused, players’ tunnel on the halfway line at Old Trafford, fragments of Goodison and Dundee’s Dens Park – are justifiably cherished by the fans of those clubs. In the case of Rangers, the famous old Leith red-brick facade has simultaneously become an all-encompassing emblem of identity, resilience and defiance for home supporters, and, for the club’s many critics, a metaphor for an antiquated institution crumbling and stumbling from one disastrous court decision to the next. In the spring of last year, my own practice, Keppie Design, was commissioned to develop the long-term design vision for Hampden Park to remain the home of Scottish football. Although nothing of the original structure now remains in place, our natural starting point was to research and analyse what the Leitch-designed stadium had originally meant to the hundreds of thousands of flat-capped fans, standing crammed, sardine-like, into open, uncovered terraces, and regularly setting world records for attendance figures that are destined to remain unbroken. In fact, one of Leitch’s original patented tubular steel terracing barriers, designed in the aftermath of the original Ibrox disaster, still features in the Scottish Football Museum at Hampden, retrieved from the concrete terracing prior to its demolition.

Many in our design team had their own unforgettable memories to draw on. I grew up just a Peter McCloy goal-kick from the ground in Mount Florida, and my first time inside it was as one of more than 30,000 there to wave a squad of tightly permed, flared-suited Scotsmen off to what was sure to be an inevitable World Cup triumph in Argentina. At the age of thirteen, I subsequently learned what it was to be Scottish; to dream unrealistically in the face of all logic. But I also experienced how a stadium’s reputation can often grow exponentially in the anticipation of a team’s success, before shrinking dramatically in the wake of subsequent failures. At any given time, a fan’s attitude to a stadium is inextricably linked to their team’s performance inside it. This led us to ponder whether Leitch’s grounds were simply more accepting of the deficits in what has become known as the fan experience. Think of those legendary ‘70s nights on the Kop at Anfield. Leitch’s ‘fan experience’ was all about the moment the ball hit the net; not the joy in realising that prawn sandwiches and vegan tofu had just been added to the match-day menus.

The game – and the way we watch it – has changed immeasurably since Archibald Leitch created those early templates. But for the modern designer the basic premise remains a very simple one: a rectangular piece of grass (or a similarly synthetic surface), a ball, eleven players on either side (unless you’re one of the growing armies of conspiracy theorists) surrounded by raking stepped platforms for spectators to watch the action unfold. Clear sightlines being the principal design consideration, form has always followed this basic function. The stadium was essentially a main stand building, containing basic changing facilities for the players, some administrative offices, and ever so slightly more comfortable seats for owners and employees of the club. Everyone else stood. Whatever the weather. As money rains down on the upper echelons of the modern game, the 21st Century football stadium must offer more. But more of what? Nowadays, the focus is on the live event: a descriptive aspiration that necessitates a life of multi-purpose entertainment uses to return the vast commercial investment for a structure that otherwise would only be in use around 20-25 times in a year. Given this perpetual financial challenge for the top clubs, it’s hardly surprising that their fans are often the last to be considered in terms of facilities, pricing and offer. Stadium design is now about maximising the corporate return. It is perhaps an uncomfortable truth that football clubs benefitting most from the increasingly exorbitant TV deals now crave subscribers more than supporters. A logical future extension of this need could see fans allowed into games in the top five European leagues for free, simply to generate crowd atmosphere for the more important target demographic watching at home.

Might it be conceivable that those enjoying the lavish hospitality at Wembley would have their empty seats filled with CGI ‘supporters’ for the first ten minutes of the second half of the FA Cup Final? Since TV is the biggest scam of all, would television audiences notice (or even care) if entire crowds were created using virtual reality green-screening?

The divergence of club fortunes in such countries sees those struggling at the bottom of the professional leagues – still playing in Leitch-influenced grounds (if they’re lucky) – desperately needing every season-ticket sold to survive, whilst those at the top view gate-money as an inconsequential drop in the ocean of their overall budget. This widening gulf represents a pivotal moment for the game. But, if progress – technological, experiential, environmental, structural – can create a vastly different viewing experience for football fans at a futuristic stadium capable of hosting a monster truck rally, an imported NFL match and an Ed Sheeran concert in the week between two packed-out football matches, then you might rightly ask … where’s the problem in that?

Football’s biggest problem isn’t the precarious financial gulf between the top 16 teams in Europe, and virtually everyone else. Paradoxically, given the vast increase in social media discussion, blogs and endless discussions that take now place online amongst thousands of anonymous strangers, its biggest challenge could be an apathy which could ultimately be fatal. The administrators, and everyone else currently drawing money from UEFA and FIFA don’t appear to care too much about its long-term future. Yet they ultimately rely on the fans – the only individuals regularly putting their own money in – to justify many of the bemusing decisions they reach about the game.

It takes a substantial amount of opprobrium being brought down on the die-hard football fan’s head for him or her to say ‘enough’. But that’s where the sport and its fractious relationship with many of those paying fans is undoubtedly heading. A football club means the most to those who take the least from it. They protest the loudest and longest, yet they rarely get properly listened to. When the paying customer loses interest, most businesses are in real trouble. When it’s in a business context as precarious as football, it will be catastrophic.

These words might seem Luddite in nature; belonging to a different era. To a different environment. Perhaps more compatible with the one in which Archibald Leitch practiced. Rather, they reflect a concern that the game – and those who design the context for it – might be losing sight of its core customer in the desire to broaden its audience and widen its appeal. Losing – or selling – its soul in the process. West Ham’s current experience in what is undoubtedly a far better-designed structure than the Upton Park that the club left behind is a salutary one that maybe makes this point more clearly than I can.

Many supporters want a return to the terraces of old, and safe-standing areas are gradually being reintroduced into some football grounds. Celtic is the most notable, and the first club in Britain to be granted a license for the type of rail seating that has been in use in several Bundesliga grounds. Although tentatively successful, such initiatives – more akin to recreating the legendary atmospheres of the Leitch-era grounds – are very small in scale, and UEFA or FIFA tournaments don’t permit anything outside of strictly all-seater stadia. Nonetheless, it is a very important step.

Our work at Hampden Park sought to foster and create the necessary revenue opportunities that a national sporting organisation needs to embrace for stability, sustainability, identity and growth. We imagined a new vision for the wider Mount Florida community that Hampden Park is a massive part of; but with a stadium environment founded upon a modern recreation of that spine-tingling atmosphere, and the building of excitement and anticipation that begins well in advance of the first whistle. One that makes people fall in love with the game again. These ambitions shouldn’t be mutually exclusive. I’m certain ‘Engineering Archie’ would’ve agreed.