Keppie at 170: The Ca’D’Oro (4 of 12)

- Written by

- David Ross

- Listed in

- Posted on

- 3rd May 2024

In the early 1870s John Honeyman received his first retail commissions. Honeyman often used cast-iron columns for galleries in churches to minimise restricted viewing, and in 1864 he used a cast-iron frame to maximise the window wall for G & J Burns warehouse at 30 Jamaica Street.

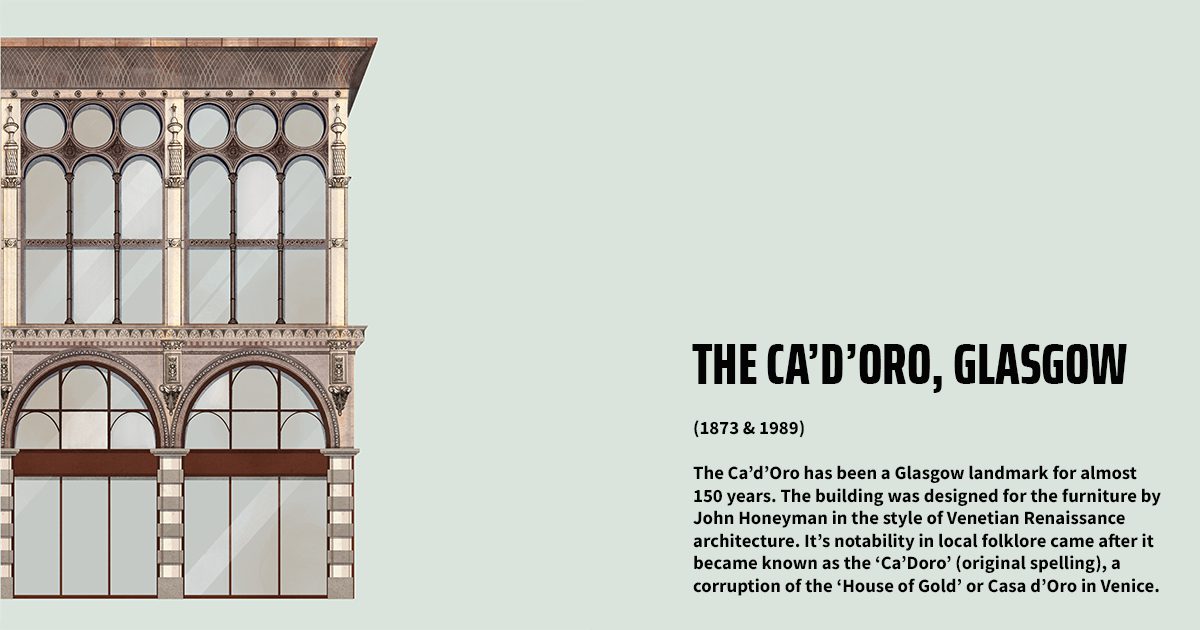

However, the furniture warehouse designed for F & J Smith at the corner of Gordon Street and Union Street produced a flourish of decorative detailing in cast iron. Both warehouses took their influence from Venice, although the latter’s arched, moulded facades are much grander.

The building was constructed at a cost of £11,000; a figure that would equate to a relatively modest £1.5m in 2024. The Ca’d’Oro’s use as a furniture store ceased in 1896, when it housed Mrs McCall’s Victorian Restaurant. In 1921, it became the flagship of the City Bakeries.

In the early 1870s John Honeyman received his first retail commissions. Honeyman often used cast-iron columns for galleries in churches to minimise restricted viewing, and in 1864 he used a cast-iron frame to maximise the window wall for G & J Burns warehouse at 30 Jamaica Street.

However, the furniture warehouse designed for F & J Smith at the corner of Gordon Street and Union Street produced a flourish of decorative detailing in cast iron. Both warehouses took their influence from Venice, although the latter’s arched, moulded facades are much grander.

The building was constructed at a cost of £11,000; a figure that would equate to a relatively modest £1.5m in 2024. The Ca’d’Oro’s use as a furniture store ceased in 1896, when it housed Mrs McCall’s Victorian Restaurant. In 1921, it became the flagship of the City Bakeries.

In the mid-20s, the Ca’d’Oro’s ground floor was fitted out with a marble shopping hall, a quick lunch counter, and a businessmen’s smoke room. Above this was a Venetian tea room, a musician’s gallery, and a series of dining and function rooms. It became a favourite place to host weddings.

The Scottish Co-Op Society took over the building after the Second World War, but it didn’t fare well and closed in 1958. Thereafter, the Ca’d’Oro was split; Reo Stakis taking the basement and upper two floors for a restaurant with four separate retail stores at street level.

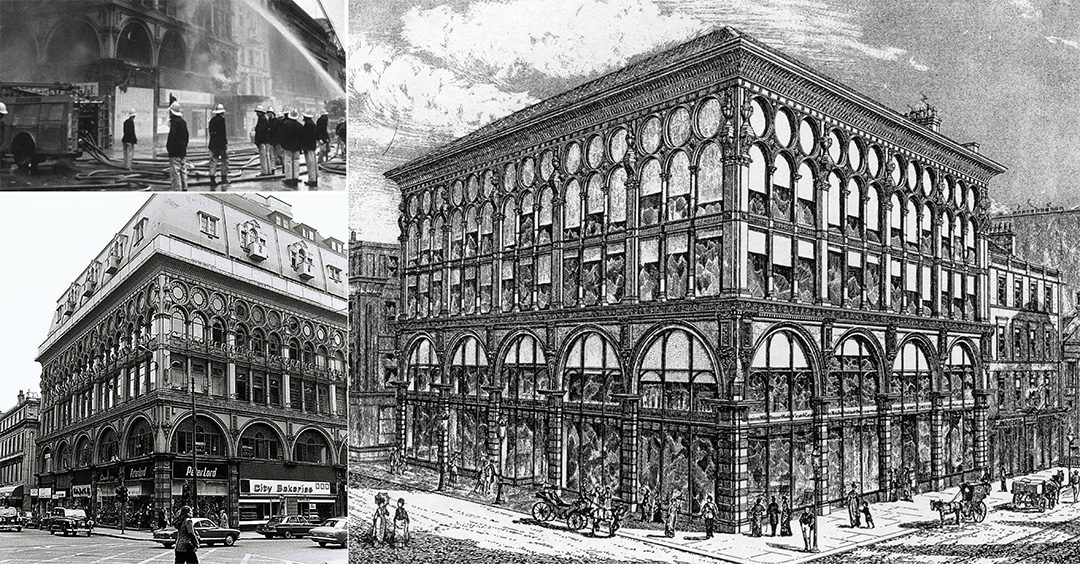

A fire in 1987 gutted the building as redevelopment plans were being prepared by Scott Brownrigg and Turner, just before the merger with Keppie Henderson. SBT Partner handed responsibility for the project to David Collin and Bill Rodger.

Client CIS Ltd owned both the Ca’d’Oro and the adjacent ‘Maison Centrale’, and knew that they possessed something special, although the latter had severe structural problems and had to be demolished. The decision was taken to extend the Honeyman building by two bays.

A mansard roof, added in the mid-20s by Jack Coia (of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia) was removed and the roof returned to its original level. Detailed explorations by a range of restoration experts were undertaken, with one paint expert scraping layers back to the primer.

This proved the theory that Honeyman’s original intention in using cast iron would have been to obtain the effect of very fine masonry at low cost by using multiple castings from a single mould. During his visit, the paint expert asked if he could see the ballroom. The once glorious space took his breath away. He later explained that the last time he had been in the building, he was playing the piano accordion in a dance band.

During the survey and research process, significant numbers of stained-glass windows were stolen. Glasgow’s intrepid thieves risked their lives on dark, wet, rooftops to strip the building of anything saleable. The stained glass is now believed to be in America. After the restoration, the building’s listing was upgraded to Category A and the project received a prestigious Europa Nostra award.

(extracts from ‘Charles Rennie Mackintosh & Co.’ by David Stark)

I first encountered the Ca’d’Oro, a soot-blackened sentinel watching over Gordon and Union Streets, as a 15-year-old, when, ahead of a school disco, my big brother and his mates snuck me into its basement bar, then called City Limits. A Chinese-run gaff, with the usual rumours of Triad links, you could eat BBQ spare ribs, pancake rolls, and crispy prawns while downing a pint.

Had I but known it, I was following in the footsteps of previous underagers, who had known the place as the Rio Stakis-owned El Guero self-service restaurant, beloved of office juniors at lunchtime, and gaggles of private school kids come 4 o’clock. It also, in the late Sixties, operated as the Bier Kellar Bar, serving strong German beer to the city’s trendies.

I can still remember exiting Central Station, from the Union Street side, and seeing the canopy, with its red Neon sign advertising ‘City Limits’. I suppose the name came from the days when the street really marked the limit of old Glasgow, with everything on the other side of the street belonging to the old village of Grahamston, which was erased from memory and city maps for the building of Central Station.

I next encountered the building in 1987, when it caught fire. I was a student, at Glasgow Tech, and out filming with some classmates. We’d just humphed all our gear to the top of Glasgow University tower when we spied a huge black smoke signal emerging from the city centre.

It read: ‘Heap big trouble in town!’.

We clattered back down the tight turnpike stair and hotfooted straight into town. With no fire cordon in place we filmed the blaze close up for about 15-minutes before the white-hatted Fire Master inquired which TV station we were from – BBC or STV? When we admitted we were just students, he literally chased us from the scene, with a few choice epithets thrown in!

As luck would have it, we ended up with the best footage of the fire, which we flogged to that night’s BBC and STV news, later retiring to the Rock Garden, in Queen Street, to drink our ill-gotten gains.

I last entered the building in 2018, when Keppie Design were having one of their regular clear outs. Gordon Watson, of the Inverness office, an old school chum, thought I might be interested in copies of the original 1920s scale plans for the addition of the rather ugly and out of style 1920’s Mansarded-roof ballroom, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, which were headed for a skip. You bet I would!

Fascinating as they were, the plans were too big, and too detailed for me to properly photograph or scan. I was stumped as to what to do with them. Then I had a bright idea.

I phoned the law firm Harper McLeod, who still occupy the building’s upper floors. As chance would have it, one of my old Evening Times/Herald colleagues was then their inhouse PR guy, and he invited me round. A cup of coffee, a handshake, and a deal was done – they’d take possession of the plans, to frame and hang on their walls, and use their giant scanner (used to scan maps in property disputes) to give me high-res copies.

As they were lawyers, with deep pockets, and the plans weren’t mine to sell, I suggested that, rather than cash, they made a generous donation to a Glasgow food bank, which they did.

The plans went ‘home’, and people were fed. That’s a win/win in my book.