Keppie at 170: Lansdowne Church (6 of 12)

- Written by

- David Ross

- Listed in

- Posted on

- 28th Jun 2024

(Image Courtesy of Natalie Tweedie)

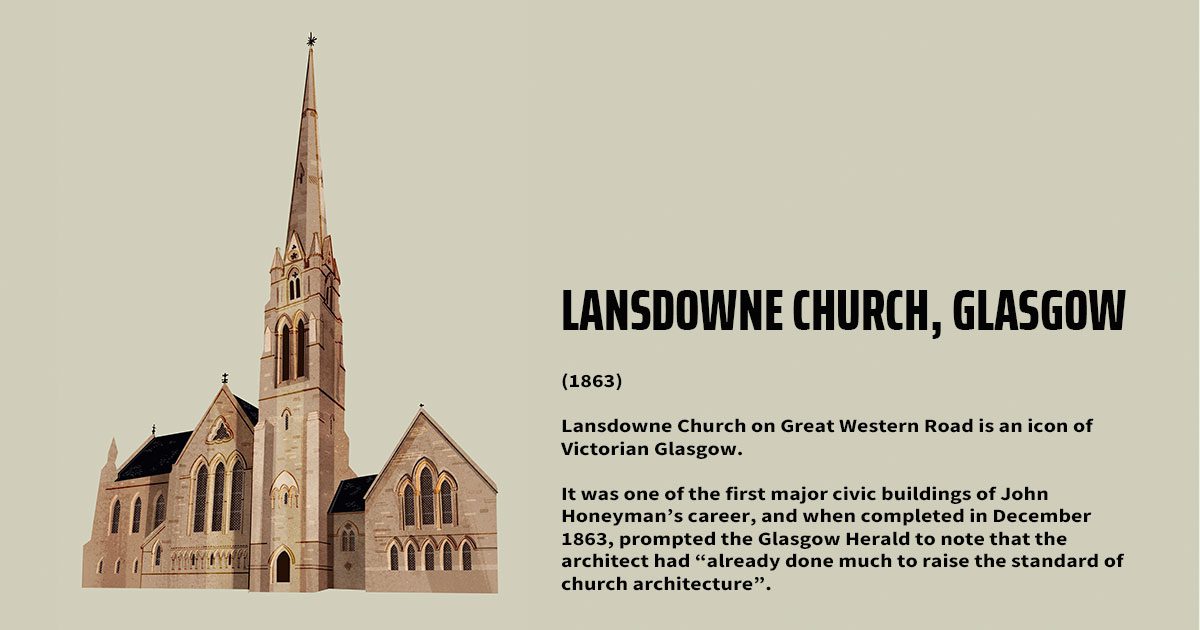

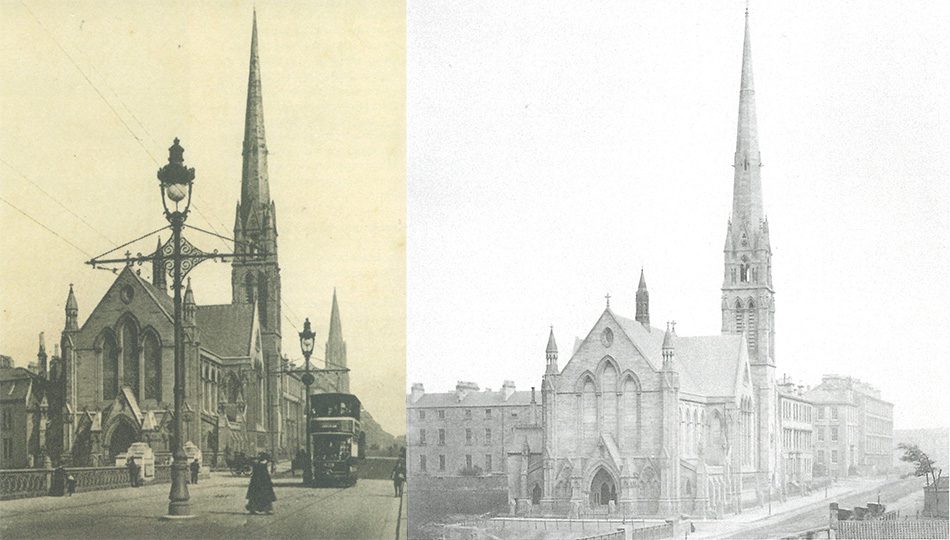

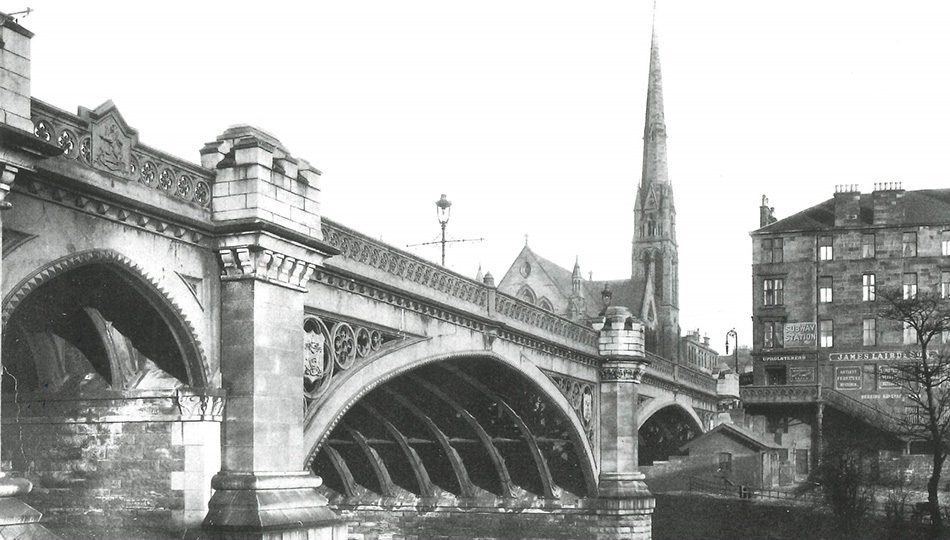

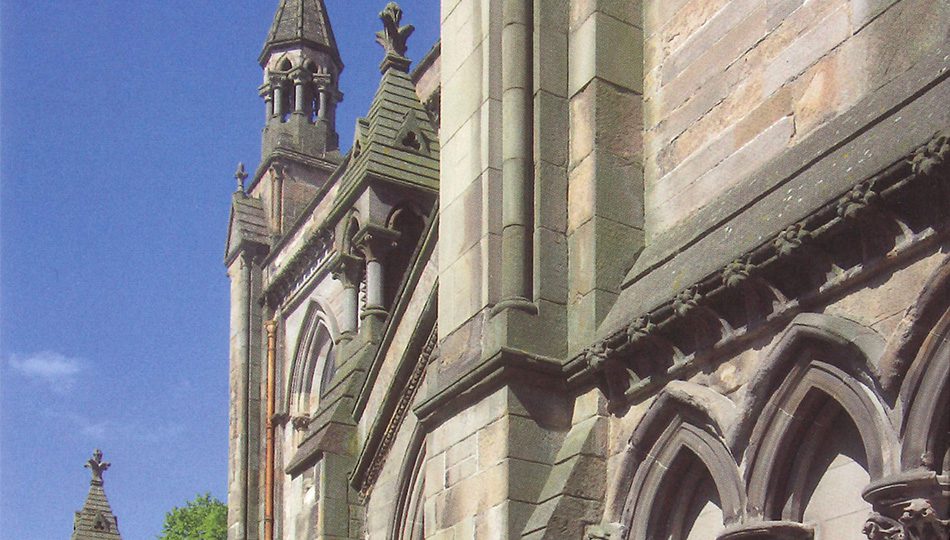

Honeyman won the commission for Lansdowne Church from a limited design competition. When it opened in 1863, it marked the western boundary of the city, with its slender spire rising 67 metres from the ground. It was founded by wealthy breakaway members of the Cambridge Street United Presbyterian Church.

Four elders and 68 members took part in the inaugural service. The collection on that Sunday amounted to the enormous sum of £1,234. The cost of the church itself was £12,563, and the debt was fully paid off by 1876.

The first minister, the Rev. John Eadie, was a colourful character, as the caricature of the time suggests. The following poem was found on the door of the church on the opening Sunday, and summed up the feelings of those who for one reason or another were excluded:

Dr Eadie was also Professor of Biblical Literature to the United Presbyterian Church and from 1870 to 1875 edited a revision of the English Bible, a copy of which is in the church. He died in 1876 and the sculptor John Mossman carved a likeness of his head above the internal doorway to the church.

The technology behind the tallest, slimmest spire in Scotland should not be underestimated. Stone, like brick or concrete, is a material which does not perform well when bent by the wind. It is strong when being compressed by a load acting vertically, but cracks or breaks when it bends and suffers tension.

To ensure that the spire doesn’t bend in the wind, there is a cast-iron rod running through its centre which is tensioned to continually pull downwards like a tent guy. The rod continues to keep the stone in compression, despite the high winds that have threatened to blow it over during the last 150 years.

Honeyman developed the layout he had used in 1861 for the Free West Church in Greenock but he introduced a semicircular barrel vault in the nave to improve the acoustics and enlarged the design to seat 1,200 people.

At this time organs were disapproved of, being regarded as ‘music hall’ entertainment. Singing was led by a precentor appointed by the Kirk Session, and the acoustics had to be good to hear him properly.

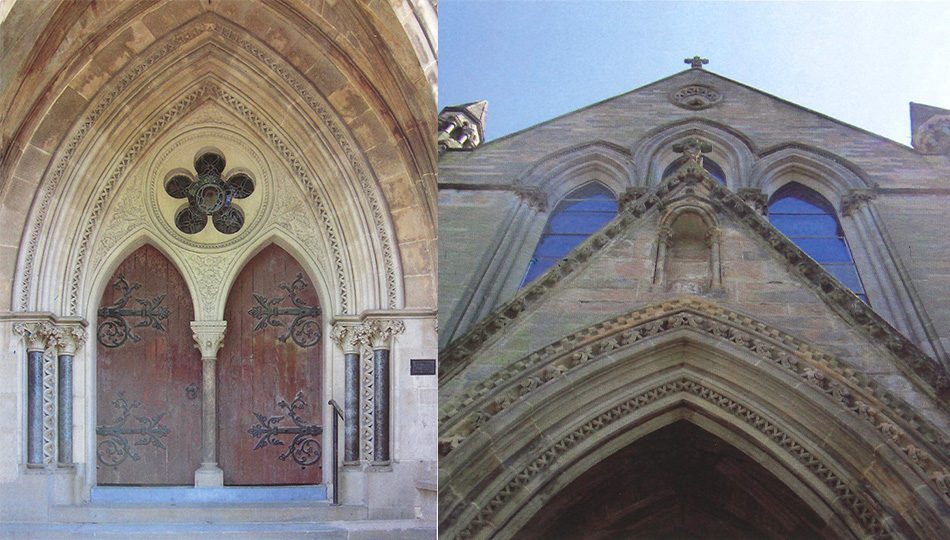

Honeyman relied a lot on the help of sculptor John Mossman and his assistant James Shanks for the stone detailing. At the south door from Great Western Road there are stone gargoyle heads, known as the ‘Lansdowne Devils’. Apparently a workman, after being sacked, cursed, ‘I’ll leave the de’il in this Kirk’, giving Mossman the inspiration for his carvings.

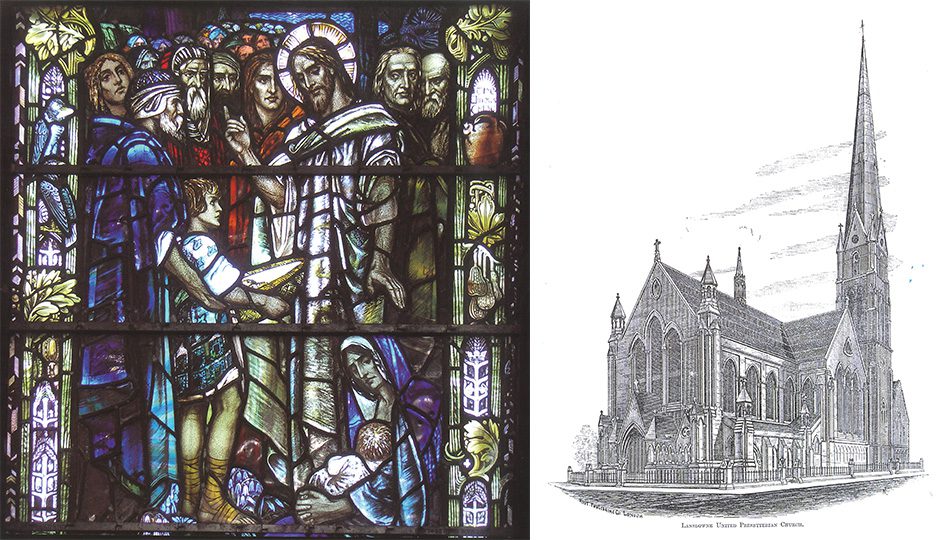

The stained-glass windows were installed later and were dedicated as a memorial to victims of the First World War; the artist, Alfred Webster, himself losing his life in the conflict. The right-hand side of one of the windows shows Jesus entering the Holy City, but the city depicted is Glasgow. The other shows St Paul preaching to the licentious Romans, but Rome is depicted as London. The artist had a sense of humour.

The original chancel has been altered over the years, the marble base for the polished pine pulpit eventually used as the communion table. Church attendance peaked in Glasgow after the Second World War but has rapidly decreased since.

In 2024, the church is home to Webster’s Theatre and the associated Webster’s Playhouse, providing arts performance and community facilities in the former A-Listed Lansdowne Church building. To find out more about the future for the building, visit https://www.webstersglasgow.com/history/

(extracts from ‘Charles Rennie Mackintosh & Co.’ by David Stark)

“As a student living just off Great Western Road in the 1970s I have a vivid recollection of suddenly being struck by the beauty of the spire of Lansdowne Church while walking from a flat in Dunearn Street towards the subway station at Kelvinbridge. Some architecture gets through the haze and demands to be noticed. Sometimes this effect is because the form is shocking or unusual. In the case of Lansdowne it happens in the same way every time because the form is so beautiful. Few examples of Victorian Gothic Revival architecture are as elegant as Honeyman’s Lansdowne now Websters Theatre.”