Keppie at 170: Glasgow Sheriff Court (7 of 12)

- Written by

- David Ross

- Listed in

- Posted on

- 2nd Aug 2024

(Illustration courtesy of Natalie Tweedie / Nebo Peklo)

As early as 1932 it was identified that the sheriff court building in the Merchant City was too small and had no room to expand. Management consultants were appointed in 1965 by the Court House Commissioners and they recommended that a new building be constructed.

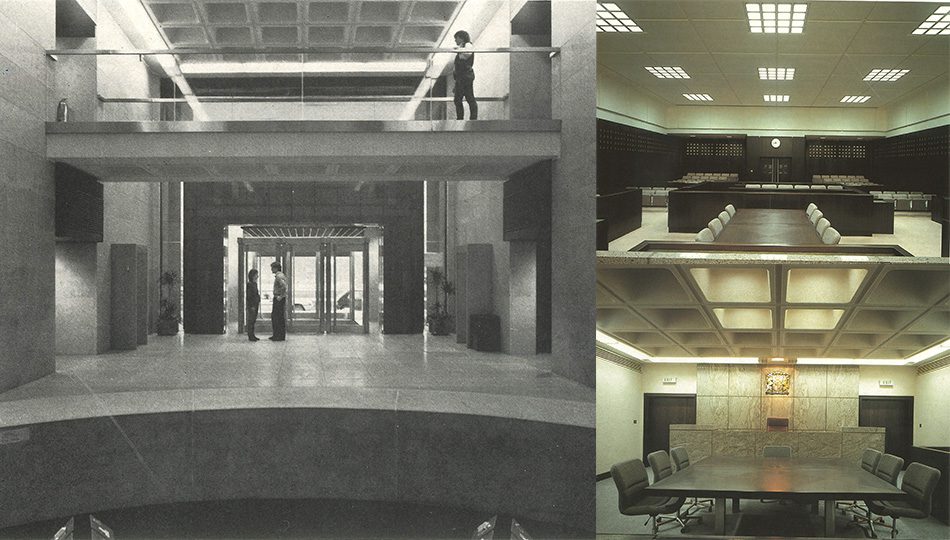

The brief for the new building included four criminal jury courts, eleven general purpose courts, a diet court (a court to debate points of law), an appeal court, two juvenile courts, a civil court, and a criminal custody court.

As there was no space large enough in the city centre to provide for what was needed, the commissioners looked south of the river where the Gorbals was being comprehensively redeveloped, or rather, obliterated.

The area had deteriorated during the 1930s recession and the post-war era, earning a reputation for its slums and No Mean City image. The chosen site for the courts was located between one which would later contain the Glasgow Central Mosque and Carlton Terrace.

Keppie Henderson were appointed as architects in 1970. Two years later, the client body changed from Glasgow Corporation to the newly formed Property Services Agency of the Department of the Environment, which was charged with providing accommodation required by the government.

Then, on 1st April 1975, the sheriffdoms of Glasgow and Strathkelvin were combined and took over responsibility. Each time the client changed, so did the requirements. Work did not commence on site until March 1979, and then only to divert sewers which would have been in the way of the building.

Proper construction work did not start until June 1981, with the ‘topping out’ ceremony being carried out on 28th September 1983 by Michael Ancram MP, then Minister for Home Affairs and Environment at the Scottish Office. Construction work finished in January 1986, but sittings didn’t commence until May 1986.

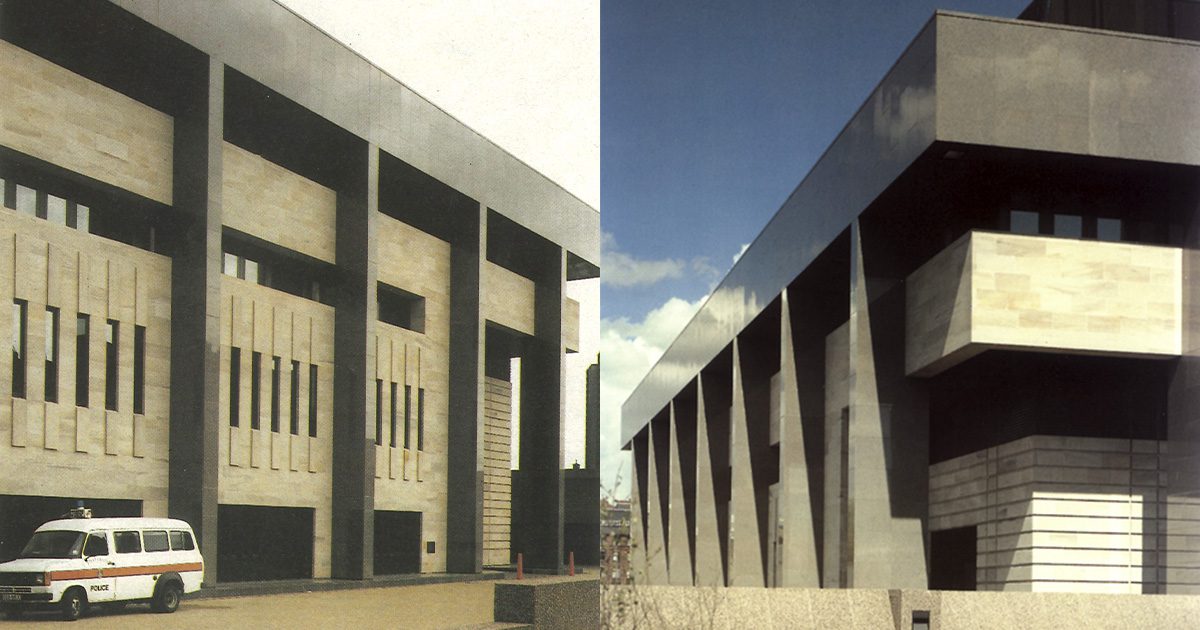

In contrast with other public buildings of the era such as schools and hospitals, the budget allowed for the best of materials. There was granite cladding from the Isle of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea, Hoptonwood limestone from Middleton Quarry in Wirksworth, and Cat Castle Quarry was specially reopened to obtain sandstone.

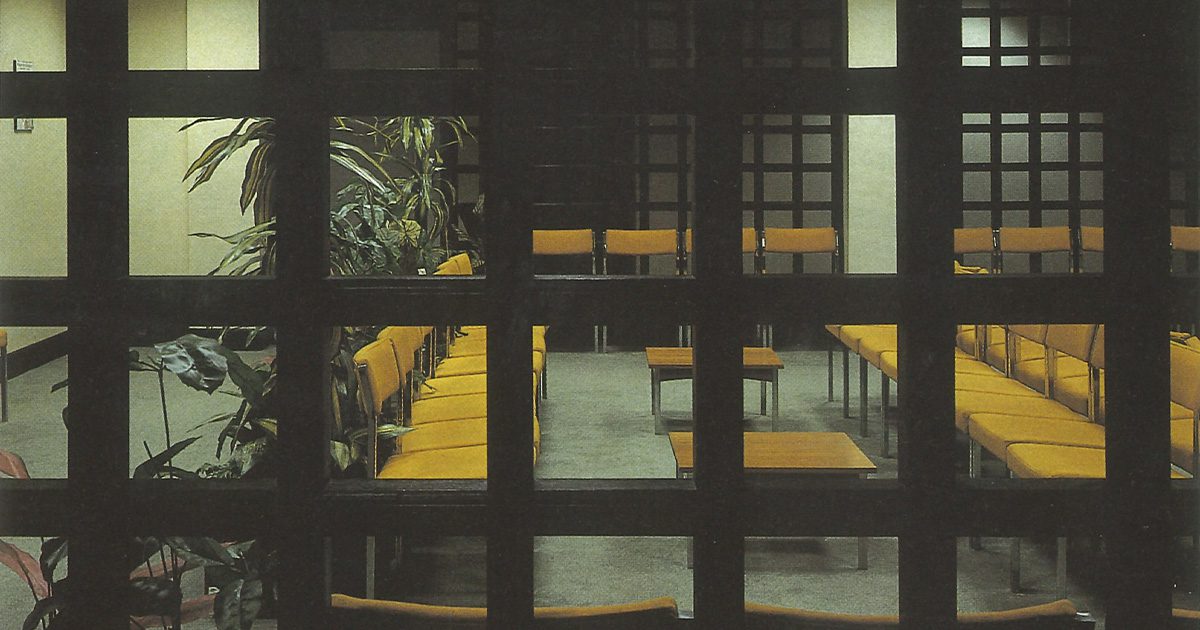

The interior was lined with wenge hardwood from Zaire, American white oak, Japanese sen ash, and most expensive of all, English brown oak was used for the shrieval chambers. In those days, people were only starting to ask if hardwoods came from renewable sources.

(text extracts from ‘Charles Rennie Mackintosh & Co.’ by David Stark)

Since it was considered important that there should be continuity of the grain pattern of the wood, each log had to be assessed to ensure that it contained enough timber for a particular room or court. Basic building costs for the five-storey building, at tender stage in December 1980, amounted to nearly £17.6m or £732.72/sqm. The final project cost in 1986 was approx. £30m.

The courts have been opened to the public on Doors Open Days, and the tour of the various parts of the building is fascinating. Even though some of its occupants are by their nature not well-behaved citizens, and it remains one of the busiest courts in Europe, it still looks as good as it did when it opened almost 40 years ago. This cannot be said for many buildings of its era.

Building Study by Jake Brown

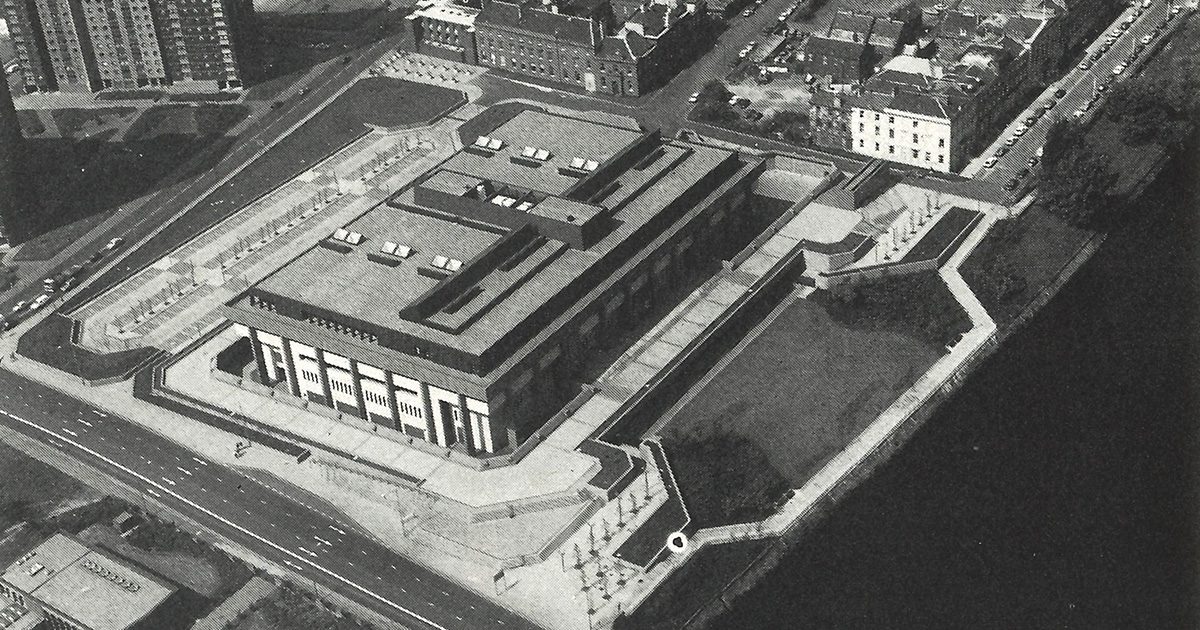

Immediately to the South a river in the heart of Glasgow, the site is bounded by a road bridge and a group of semi-derelict buildings behind the partially refurbished Carlton Terrace. Another road at the rear separates it from two huge tower blocks while the view over the Gorbals includes, at not too great a distance, an abandoned slab of medium-rise housing. Midway through the design stage a substantial increase in accommodation was required. This and advice from the Royal Fine Art Commission for Scotland led to the building being set well back from the river in the centre of the big rectangular site. The raised fire access road at the rear with the terracing and steps at the front eased the introduction of the security moat, having the effect of placing the building mass on an apparent knoll.

However, the outcome of all this design for security was to focus the eye on the structure as an isolated monumental statement. The importance of the view across the Clyde has been recognised and presumably the strong scale and symmetry are a response to this. The powerful structural framework features a huge capping beam/cornice supported by deep columns. This is faced with a dark greyish/pink granite from the Moselokke quarry on the Danish island of Bornholm. Set within this and given the same uninterrupted horizontal emphasis is a subsidiary apparent structure, faced with pale sandstone, and having greater cantilever beams at the corners. The river face is set back yet again with two floors having strongly emphasised coursing.

Close to these facades the quality of materials is impressive. At a distance, however, the vigorous frame becomes ponderous, the ring beam being assertive enough to have industrial connotations, while the suppression of the fenestration into slits is suggestive of the blind face of a stadia building.

The atrium, such a successful and significant space within, is given no expression on the building face. The potential tyranny of symmetrical design has had its way here – the atrium sharing a few modest vertical slits with adjacent tiny witness waiting rooms at plan level two.

As indicated initially, law courts are normally part of a conscious urban development, but there is little sign of this here. The urban context, manifestly beyond the control of the architects, has all the glamour of that of a peripheral hypermarket. Despite the boldly modelled boundary walls and ancillary building with its emphatic granite face bearing the incised building title the general surroundings bear all the hallmarks of a ‘security scape’.

Can Glasgow afford to wait in the manner of many medieval and Renaissance civic buildings for a slow enclosing development over decades or even centuries, or is the contrast between this palace of law and order and the civic and social breakdown around it too pointed? It is fair to recognise that when and if the trees and planting associated with the riverside walk are mature this situation will be improved. At the moment, however, this building adds another example to the lacunae of urban planning in the UK.

(This extract is taken from an extended building appraisal by Jake Brown. First printed in The Architects’ Journal, 11th February 1987)